Keith Haring was a street artist at the heart of the urban art movement in 1980s New York. He was also a gay man diagnosed with AIDS. Partly as a result of living with these stigmas, his work often bears a strong element of political and social critique.

He was one third of a trio of New York street artists at the helm of the growing movement. He, Richard Hambleton and Jean-Michel Basquiat regularly met to discuss each other’s work, and sometimes collaborated.

He first began using public spaces as his canvas whilst studying at New York’s School of Visual Arts, when he started drawing on blank advertising panels in subway stations.

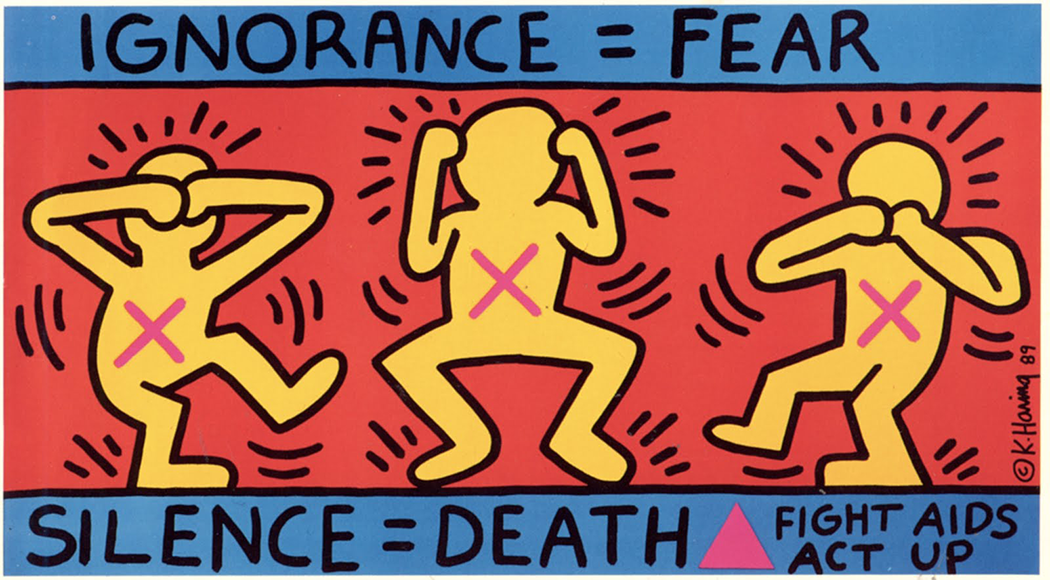

Whimsical human figures drawn in bold and clear outlines became his trademark. They contrast with the heavy subject matter of much of his work. In his art he called attention to the AIDS epidemic afflicting gay men in the 1980s.

He made his targets state and society. The Reagan and Bush administrations neglected to fund research into treatments and a cure for the disease. This negligence left AIDS sufferers in the dark, without support, whilst religious leaders and the media continued to blame gay men for the problem.

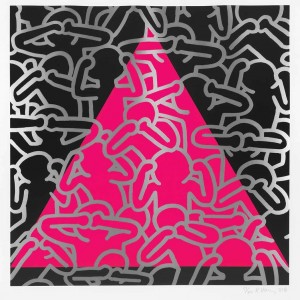

One of his most famous works is a commentary on the epidemic called Silence=Death, which depicts a crowd of figures covering their ears as if to avoid the horrible truth of AIDS. Overlaying the crowd is a pink triangle. The Nazis gave this symbol in the form of a badge to concentration camp inmates imprisoned for their sexuality. The symbol was reclaimed by the gay community in the 1980s.

In the mid-80s Haring set up ‘pop shops’ which sold his imagery on t-shirts, buttons, bags and stickers. The shops made his work accessible at low cost to everyday people and were an innovative way of disseminating pop art.

After he was diagnosed with AIDS in 1987, Haring felt a renewed determination, sensing the urgency of his work.

Some critics described his art as freer after his diagnosis. Robert Farris Thompson wrote that “in his art he found the key to transform desire, the force that killed him, into a flowering elegance that will live beyond his time.”

He died in 1990 as a result of AIDS-related complications. But his work lives on, his figures still a recognised visual language in the 21st century.